| Home |

| About Us |

| The Dublin Court |

| The Irish Real Tennis Championships |

| The Game of Real Tennis |

| News |

| Links |

| Contact Us |

| Privacy Statement |

The "Lost" Court of Cumberland Islandby Dennis McCarthy |

|

A Tale of Two Courts

|

Squash Tennis Anyone?

The origins of squash tennis, though not definitively documented, are surely not as obscure as court tennis (also real tennis or, properly, just tennis). The idea for the game probably began in Concord, New Hampshire in 1883 when St. Paul's School students carried lawn tennis equipment onto their new rackets courts while waiting for the proper equipment to be shipped from England.1 Apparently even years later they occasionally used the "wrong" equipment both on the school's rackets courts and newer squash racquets2 courts.

|

Lost and Found

Finding the Plum Orchard court was not easy. But exactly how does a nearly 500 square foot space in a grand mansion get lost? It mostly hinges on the remoteness of the estate, and the changing meaning of the word "squash."Large tracts of Cumberland Island, off the southern tip of Georgia's Atlantic coast, had been purchased for winter estates during America's Gilded Age. Certain families rode the crest of the industrial revolution from their Park Avenue residences to their summer mansions in Newport, and then to winter estates in the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida—at least until new income tax and anti-monopoly laws caught up with them. On Cumberland Island most of this land was left wild either for hunting or for scenic value. The island was remote, and remains so today. There never has been a bridge to the mainland, and few reside there. In the 1970s, after a similar barrier island in South Carolina was "developed" beyond recognition, activists started to look for ways to protect Cumberland Island. The federal government became interested in turning the island into a protected natural area, and either by purchase or donation most of the island is now Cumberland Island National Seashore, administered by the National Park Service (NPS). A maximum of 300 visitors per day may take the ferry to Cumberland Island, which is 17½ miles (28 km) long totaling 36,415 acres (14,737 ha), including 16,850 acres of marsh, mud flats, and tidal creeks.

After my only visit to the island (that unfortunately did not include Plum Orchard), the architect in me became somewhat curious of the history of its estates. With a little research I found the copies of the original plans for Plum Orchard that included a room labeled simply "squash court." I had vaguely heard of squash, but as it meant little to me at the time I filed the court away in my memory. A few years later I was browsing through a 1932 book of architectural standards that included dimensions for a regulation "squash tennis and squash racquet court." By then the National Squash Tennis Association had authorized play on an 18½' by 32' American (hardball) squash racquets court—with a few extra lines added to the floor and back wall.12 This, coupled with the decline in numbers of squash tennis players, meant that virtually all 17' wide squash tennis courts were doomed to demolition or alteration.

|

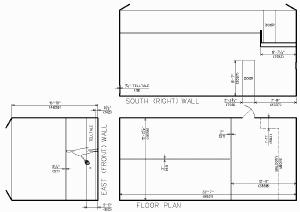

I went back to the Plum Orchard plans and began to recognize some odd features of this court. It was planned to be only 16' wide, but 34' long. The door, rather than being in the middle of the back wall, is on the right wall near in the back-court, and the gallery is actually a balcony that projects into the court. Unfortunately, the construction drawings did not include any playing features that might positively identify if this is a squash tennis versus a squash racquets court, and I could find no clear photographs of the court.13 The building's Historic Structure Report (a public document cataloging architectural features and conditions) only included language on the court's balcony, windows, and construction—not a mention of the lines or playing features, nor what "squash" meant to the original architect. After writing to the park, I was sent a sketch that showed the floor lines: no service boxes, and a "T" of which the center-court line runs to the front wall rather than the back—something that only makes sense for the fore-court serve of squash tennis. Eureka!—I had finally "found" this lost court.

Degrees of Loss

Recently I was put in touch with Tom Murphy, an NPS architect based in Denver involved in a preservation project at the estate. Having played both squash racquets and lawn tennis (but like the staff of Cumberland Island National Seashore, never having heard of squash tennis) he quickly agreed to take some photographs and measurements for me. Some additional information from the park's facility manager, David Casey, and a park volunteer, Bernard Huber, completed the rediscovery. |

A clue behind this alteration can be seen in one of the photographs: an old wooden racquetball racquet, not listed in the 1972 inventory. Even though the estate was closed to the public, early on, after transfer of the estate to the NPS, the doors were apparently not locked very well and the stray visitor, employee, or island resident, could find his way into the mansion. Racquetball became popular in America around 1970, but required a court with bare walls. Someone may have removed the telltales for this purpose. A less mischievous explanation is that the telltales were removed to inspect the condition of the walls, and simply were never reinstalled—then someone took advantage of the bare walls to play some racquetball.

Yet, even if the telltales had been lost, this would have been minor, due to the fact that the wood around the telltales was bleached in the sun. The former locations of the telltales are still easily visible. As such, the court is effectively playable today as-is, although an occasional dispute could occur when a shot is close to being out. Luckily no one painted additional lines on the floor or walls for playing squash racquets or racquetball. A major loss is the story of Cumberland Island's other squash tennis court. The second, and slightly earlier, court was located in the recreation building of the Dungeness estate, owned by Lucy Coleman Carnegie, George's widowed mother.18 This court did not need a back telltale—above 5' the back wall was wire mesh for viewing—perhaps inspired by court tennis' netted gallery openings, and a thematic precursor to today's glass-walled squash courts. The Dungeness mansion burned down in 1959. The associated outbuildings of the estate, such as the recreation building, became seriously neglected. By the time the NPS had established itself on Cumberland Island, the building containing the Dungeness squash court had serious structural problems. It collapsed around 1982.

The Irish Connection

Besides some coincidental similarities in court design illustrated in the beginning of this article, the big question is: What does any of this have to do with the Irish Real Tennis Association (IRTA)? Consider some lessons of the courts of Cumberland Island:The Public Trust. Both the Plum Orchard and Dublin courts are public property, and their preservation or use can be influenced by the citizenry through lobbying and education. The IRTA demonstrated this in its successful fight to prevent the permanent alteration of the court into a concert facility. If Cumberland Island had not been conserved as a National Seashore, the area would probably have been developed into gated subdivisions of vacation condominiums—who knows to what use Plum Orchard estate would have been converted into? The NPS has been looking into possible uses for Plum Orchard, including leasing, but by law preservation of its character defining historic features must be part of any planned rehabilitation work. With this research, identifying the rarity of the squash tennis court, its playing features will likely remain untouched.

Durability. The Dublin court was built as a world class facility, for year-round play, with brick and stone. The Cumberland Island courts were built of wood and plaster for the occasional match during the family's winter stay on the island. Dublin can have a thriving tennis club after removal of the inserted laboratories and restoration of the galleries. But at best Plum Orchard could host the occasional demonstration match to educate the occasional park visitor; constant club play would likely be too much for its wood frame construction. The Dungeness court has already become a victim of its maintenance intense design.

Isolation. Remoteness can be a friend and foe to preservation. For Dungeness it meant catastrophic loss. For Plum Orchard it meant survival. The reason why very few, if any, playable pure squash tennis courts remain is mostly due to competition for the space. Manhattan rents and property taxes do not permit 550 square feet to sit idle. Even the last court at the Yale Club of New York City, the home of squash tennis championships for years, recently has fallen prey to "renovation," and the space now houses exercise machines.19 But this isolation for Plum Orchard has come at the cost of near uselessness: even if squash tennis were a popular sport generally, a self-sustaining facility is impossible on a remote island. And even if the NPS allowed the public to play freely on the court, as a practical matter it would still be quieter than the wilderness around it. The Lambay Island tennis court suffers from similar curses and blessings of remoteness. This private court has not been converted to another use, but given its location 3 miles off Ireland's east coast, neither will it ever see a thriving tennis community. The court in the heart of Dublin suffers no problems of isolation, rather it has the opposite problems. It is so central that the building has been appropriated for other uses since the day the government received it. Although the IRTA has defended one challenge against restoration of the facility, University College Dublin is still using the space. Yet with this centrality comes hope for vitality—easy access for Dubliners and visitors alike. And the Dublin court has a history of world championship play.20 This combination of history and possibility has gained the IRTA supporters both at home and abroad.

Ultimately we are left with the two courts. Plum Orchard is public, isolated, playable (within limits), yet a relic of times past. Dublin is public, accessible, not playable, but durable and hopeful. One is well preserved. The other has great potential. A hundred years from now, into which court will two players walk, ready to contest a match, carrying tennis racquets and a felt-covered ball?

2004 February 10

Mr. McCarthy is an architect, living and working in Atlanta, Georgia, USA. In a comedy of errors, he somehow recently won what are probably the first three (and, simultaneously, possibly the last three) squash tennis matches ever contested at his downtown athletic club.21 With questions or comments he invites the reader to contact him at: racket@lakeclaire.org

Footnotes

- James Zug, Squash: A History of the Game (New York: Schribner, 2003), p. 21.

- Squash racquets is today usually simply called "squash." As the reader will see, the evolving terminology of these sports plays a role in the history of the Plum Orchard court.

- See Appendix A: Rules of Squash Tennis, and Appendix B: Court Diagrams

- Dick Squires, The OTHER Racquet Sports (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1978), p. 79.

- "Ridgemere," the Newport, Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, home of court tennis patrons Jay & Susie Schochet, was also designed by Peabody & Stearns.

- David G. Henderson, Plum Orchard Historic Structure Report (Denver: National Park Service, 1977), pp. 1 & 39.

- Sarah Olson, Plum Orchard Historic Furnishings Report (Harpers Ferry: National Park Service, 1988), pp. 119-120.

- Metric equivalents are included in Appendix B: Court Diagrams.

- Richard C. Squires, Squash Tennis (1968), p. 15.

- Telephone interviews with Bill Rubin [squash tennis player since the 1960s, past president of the NSTA, top seeded player in 1981, and at least twice runner-up to the national championship title (1980 & 1981)], New York, 2004 Jan 07 & 23. He also stated that the National Squash Tennis Association has not met in years. Although a search of the New York State website still listed the NSTA as an active not-for-profit corporation, no contact information is in the database.

- See Appendix C: Squash Tennis National Champions.

- Charles George Ramsey & Harold Reeve Sleeper, Architectural Graphic Standards for Architects, Engineers, Decorators, Builders, and Draftsmen (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1932), p. 173.

- The photographs in the available copy of the 1977 Historic Structure Report were illegible. I subsequently located an original with color photographs, three of which I have included here. The photograph of the façade of the mansion was taken during the past few years by the National Park Service.

- By later rules of the sport, the rear telltale would be obsolete, as a ball that first bounces on the floor is still in play even if it hits the rear wall above the back wall boundary line. If it hits the gallery or other obstruction a let is called. National Squash Tennis Association, 1967-1968 Yearbook, p. 11, rule 7(c).

- Olson, p. 153.

- Olson, pp. 142 & 144.

- Henderson, Plum Orchard HSR, p. 18.

- David G. Henderson, Dungeness Recreation/Guest House Historic Structure Report (Denver: National Park Service, 1977), pp. 1-2 & 31-32. This court was 32'-5" by 16'-5" with plaster walls. Based on historic photographs, the telltale was approximately 24" and the service line 72" from the floor; playing height on the side walls was about 11'-5". The floor lines appeared to be comparable to those of Plum Orchard. The wire mesh appeared to have been too wide to prevent a squash ball (1½″ or 40mm) from passing through.

- Rubin. This was an 18½' by 32' modified hardball/squash tennis court with a large spectator gallery.

- In 1890 Tom Pettitt defended his title against Charles Saunders in 12 sets. See the article, The 1890 World Championships, at the IRTA website, http://www.irishrealtennis.ie/

- He happened to play two other gentlemen of Irish ancestry. The scores: against Mr. T. McCarthy 15/7, 12/15, 15/6, 15/4; and against Mr. Martin 15/7, 18/13, 15/10 and 15/9, 18/17, 18/14.

Appendix A: Rules of Squash Tennis

Notes:- Information in brackets is not original to the text.

- The scoring system in these rules, from 1968, differs from those of a hundred years ago. Originally only the server could score. If the receiver won a rally, he earned the right to serve.

- The court dimensions in Rule 1 are included in Appendix B: Court Diagrams, below. Standard courts were rare enough by 1968 that these rules reference the "16-ft." line on the front wall, although on a standard squash tennis court the front-wall boundary line is 14' from the floor. The line on an American (hardball) court is 16' from the floor.

- As the added note indicates, the squash racquets court mentioned in Rule 1 is an 18½' by 32' hardball court. Squash tennis can be played on a 21' by 32' international (softball) squash racquets court if an additional floor service line is added 10' (3048mm) from the back wall, and additional back wall line is added 4'-6" (1372mm) from the floor. Masking tape can be used to temporarily add these lines. However, players insist that the change in shot angles and distances on a 21' wide court makes for a distinctly inferior game.

- As there are no longer any manufacturers of squash tennis equipment, players use lawn tennis balls and junior lawn tennis racquets. Colored (non-white/yellow) balls are preferred for visibility if the court has white walls.

OFFICIAL PLAYING RULES

1. COURTS

The court dimensions, lines, telltale, material,

construction, and lights shall be in accordance with the

specifications approved by the Executive Committee of the

National Squash Tennis Association. Existing [American

(hardball)] Squash Racquets courts are recognized by the National

Squash Tennis Association, but a court boundary line across the

back wall, 4'6" [1372mm] from the floor, is essential, and a line

from the center of the service line forward to the front wall is

highly desirable.

2. RACQUET AND BALL

The racquet or bat shall have a frame similar in shape to

that of a lawn tennis racquet, the length including the handle

not to exceed 27 inches [686mm]. The stringing shall be of gut,

nylon or other kindred substance, but neither the frame nor the

stringing may be of metal.

The ball shall be in accordance with the specification

approved by the Executive Committee of the National Squash Tennis

Association.

3. GAME

A game shall be fifteen points; that is, the player scoring

fifteen points will win the game, except in the event both

players tie (a) at "thirteen all", the player who has first

reached the score of thirteen will elect one of the following

before proceeding with the game: 1) "set five"--making the game

eighteen points, 2) "set three"--making the game sixteen points,

3) "no set"--making the game fifteen points--or b) at "fourteen

all", providing the score has not been "thirteen all", the player

who has first reached fourteen points will elect one of the

following before proceeding with the game: 1) "set three"--

making the game seventeen points, 2) "no set"--making the game

fifteen points.

4. MATCH

Matches shall be the best three out of five games.

5. SERVER

Before a match begins, it shall be decided by a spin of a

racquet by the players as to which player shall serve first.

Thereafter, when the server loses a point, his opponent becomes

the server. The winner of a game shall serve first at the

beginning of the following game.

6. SERVICE

The server shall stand behind the service line with both feet

on the floor and not touching or straddling the line, and serve

the ball against the front wall above the front-wall service line

and below the 16-ft. [4877mm] line before it touches any other

part of the court, so that it shall drop directly, or off the

side wall, into his opponent's court in front of the floor

service line without either touching the floor service line or

the center line.

If the server does not so serve, it is a fault, and if it be

the first fault, the server shall serve again from the same side.

If the server makes two consecutive faults, he loses that point.

The server has the option of electing the side from which he

shall commence serving and thereafter, until he loses the

service, he shall alternate between both sides of the court in

serving. If the server serves from the wrong side of court,

there shall be no penalty and if the receiver makes no attempt to

return the ball the point shall be replayed from the proper

court.

When one service fault has been called and play for any

reason whatsoever has stopped, when play is resumed the first

fault does not stand and the server is entitled to two services.

7. RETURN OF SERVICE AND SUBSEQUENT PLAY

(a) To make a valid return of service the ball must be

struck after the first bounce and before the second bounce, and

reach the front wall on the fly above the telltale and below the

16-ft. line; in so doing it may touch any wall or walls within

the court before or after reaching the front wall, except as in

(e), below. A service fault may not be played. If a fair

service is not so returned, it shall count as a point for the

server and he shall then serve from the other side of the court.

(b) After a valid return of service, each player alternately

thereafter shall strike the ball in the same manner as on the

return of service, except that it may be volleyed. The player

failing to so return the ball shall lose the point.

(c) A ball striking the ceiling or lights or on or above any

court boundary line on the fly shall be ruled out of court; if a

ball should strike the back wall on or above the 4'6" line after

having bounced, it shall continue to be in play. If a ball

having bounced should go into the gallery or strike any

construction which alters its course, a let shall be called.

(d) If a ball before the second bounce hits the front wall

above the telltale for the second time it is still in play.

(e) In an effort to return the ball to the front wall by

first hitting to the back wall, the ball may not be played to the

back wall unless it has first struck the back wall, and must be

so struck as to hit the back wall below the 4'6" line.

(f) A player may not hit a ball twice during a stroke, but,

while the ball is still in play, it may be struck at any number

of times.

8. LET

A "let" is the stopping of play and the playing over of the

point.

(a) In all cases, a player requesting a let must make his

request before or in the act of hitting the ball. If a let is

requested after the ball has been hit, it shall not be granted.

(b) If a player endeavoring to make his play in proper turn

is interfered with so as to prevent him from making such play as

he would without such interference, or if the striker refrains

from striking at the ball because of fear of hitting his

opponent, there shall be a let whether the ball has been hit by

him or not.

(c) A player shall not be entitled to a let because his

opponent prevents him from seeing the ball, provided his stroke

is not interfered with.

(d) If the ball breaks in the course of a point, there shall

be a let. If a player thinks the ball has broken while play is

in progress, he must nevertheless complete the point and then

request a let. The referee shall grant the let only if the ball

proves in fact to be broken.

(e) If in the course of a point either player should be

interfered with by elements outside their control, there shall be

a let.

(f) It shall be the duty of the referee to call a let if, in

his opinion, the play warrants it. If a match be played without

a referee, the question of a let shall be left to the

sportsmanship of the players.

(g) A player hit by a ball still in play loses the point,

except that if he be hit by a ball played by his opponent before

the ball strikes the front wall above the telltale, then it is a

let. If however, a player is hit by a ball off his opponent's

racquet that is clearly not going to reach the front wall above

the telltale, a let will not be allowed and the point shall be

given to the player who was hit by the ball. However, a player

hit by a ball still in play will not lose the point if because of

interference a let is called.

9. PLAYER INTERFERENCE

Each player must stay out of his opponent's way after he has

struck the ball and (a) give his opponent a fair opportunity to

get to and/or strike at the ball and (b) allow his opponent to

play the ball from any part of the court to any part of the front

wall or to either side wall.

10. LET POINT

(a) A "let point" may be called by the referee if after

adequate warning there is no attempt or evidence of intent on the

part of a player to avoid unnecessary interference or unnecessary

crowding during his opponent's playing of a point. Even though

the player is not actually striking at it, the referee may call a

let point. The player interfered with wins the point.

(b) If in the opinion of a player he is entitled to a let

point, he should at once appeal to the referee whose decision

shall be final, except when judges are present, as described in

Rule 11(b).

(c) A let point decision can only be made when a referee is

officiating.

11. REFEREE AND JUDGES

(a) If available a referee shall control the game in any

scheduled match. His decision is final, except when there are

judges present as described in Rule 11(b).

(b) Two judges may be appointed by the referee or tournament

committee to act on any appeal by a player to the referee's

decision. When such judges are on hand, a player may appeal any

decision of the referee directly to the judges. Only if both

judges disagree with the referee will the referee's decision be

reversed. The judges shall not make any ruling unless a player

makes an appeal. The decision of the judges shall be announced

promptly by the referee.

(c) All referees must be familiar with these playing rules

when officiating in sanctioned matches.

12. GENERAL

(a) At any time between points, at the discretion of the

referee a new ball may be put in play at the request of either

player.

(b) Play shall be continuous. Between the third and fourth

games there may be, at either player's request, a rest period not

to exceed five minutes. Between any other games there may be, at

either player's request, a rest period not to exceed one minute.

(c) If play is suspended by the referee due to an injury to

one of the players, such player must resume play within one hour

or otherwise default the match.

(d) The referee shall be the sole judge of any intentional

delay, and after giving due warning he may disqualify the

offender.

(e) If play is suspended by the referee for some problem

beyond the control of both players, play shall be resumed

immediately after such problem has been eliminated. If cause of

the delay cannot be corrected within one hour, the tournament

committee and/or the referee will determine when play will be

resumed. Play shall commence from the point and game score

existing at the time the match was halted.

January 1968

Source: National Squash Tennis Association, 1967-1968

Yearbook.

Appendix B: Court Diagrams

See attached Adobe Acrobat file.

Appendix C: Squash Tennis National Champions

1911-1912 Alfred Stillman 1913 George Whitney 1914 Alfred Stillman 1915-1917 Eric S. Winston 1918 Fillmore Van S. Hyde 1919 John W. Appel, Jr. 1920 Auguste J. Cordier 1921 Fillmore Van S. Hyde 1922 Thomas R. Coward 1923 R. Earl Fink 1924 Fillmore Van S. Hyde 1925 William Rand, Jr. 1926 Fillmore Van S. Hyde 1927-1929 Rowland B. Haines 1930-1940 Harry F. Wolf 1941 T. A. E. Harris 1942-1945 (no tournaments held) 1946 Frank R. Hanson 1947 Frederick B. Ryan, Jr. 1948-1950 H. Robert Reeve 1951 J. T. P. Sullivan 1952 H. Robert Reeve 1953 Howard J. Rose 1954-1956 H. Robert Reeve 1957-1959 J. Lennox Porter 1960-1962 James Prigoff 1963 John Powers 1964 James Prigoff 1965 (no tournament held) 1966-1968 James Prigoff 1969-1980 Pedro A. Bacallao 1981 David Stafford 1982-1983 Gary Squires 1984 Loren Lieberman 1985 Gary Squires 1986 Pedro A. Bacallao 1987-2000* Gary Squires* The championship tournament may not have been held every year in the early 1990s. And although (as of early 2004) the most recent tournament was held around 1995, the National Squash Tennis Association considered Gary Squires to be the reigning champion when it reported to the New York Times through 2000 for the paper's annual comprehensive list of national sports champions.

Sources. To 1967: National Squash Tennis Association 1967-1968 Yearbook. 1967-1985: Library of Bill Rubin. 1986: Sports Illustrated, 1986 Jun 02, pp. 16-17 (50 year old Mr. Bacallao, who returned to competition for the first time since 1980, beat 27 year old Gary Squires in straight games). 1987: Interview with Bill Rubin, no written record available (Mr. Rubin recalls that Mr. Squires beat Pedro Bacallao for the first time in the last match they played against each other). 1988: Library of Bill Rubin. Post 1988: New York Times' list of national champions, published in the sports section either the first or last Sunday of the year since 1989 Dec 31.