| Home |

| About Us |

| The Dublin Court |

| The Irish Real Tennis Championships |

| The Game of Real Tennis |

| News |

| Links |

| Contact Us |

| Privacy Statement |

Planning Application affecting Dublin Real Tennis CourtIRTA Submission: 31 March, 2016 |

|

The following observation was submitted by the IRTA to Dublin City Council with regard to this planning application. Formatting adjusted slightly for web presentation.

Dublin City Council Planning Department,

Civic Offices, Wood Quay, Dublin 8.

31st March 2016

Re. Planning Application Reference Number 2362/16

Location: The National Concert Hall, Earlsfort Terrace, Dublin 2.

Applicant: The Commissioners of Public Works in Ireland

Dear Sir or Madam,

The Irish Real Tennis Association (‘IRTA’) exists to promote, encourage, facilitate, and provide for the playing of the game of Real Tennis in Ireland and by Irish people.

The IRTA makes the following observations regarding the above Planning Application Reference Number 2362/16:

INTRODUCTION

1. The IRTA

The Irish Real Tennis Association was set up in 1998 and has since 2003 organised an annual Irish Real Tennis Championship tournament, held abroad as there is no playable court in Ireland. As well as the annual tournaments, the IRTA arranges occasional matches, and introductory weekends, to permit Irish players the opportunity of time on court. The Association has some 300 members, including Irish and non-Irish enthusiasts for the game, resident in Ireland or elsewhere.

The IRTA desires the restoration of the Earlsfort Terrace Real Tennis court to play.

2. The game of real tennis

Real tennis is the original racket sport from which lawn tennis, squash, badminton and other games developed. It emerged in continental Europe in medieval times, and has enjoyed fluctuating popularity over the centuries — in places it was so popular that it was outlawed, as it was considered too great a distraction from productive work. It had a resurgence in the later 19th century, when the Earlsfort Terrace court was built, and recent decades have also seen growth: there are currently some 45 courts in active use around the world, in Australia, France, the UK, and the US. Several of the courts now in use were built or refurbished over the last 25 years or so; further courts are planned or under construction.

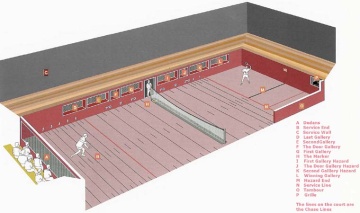

While real tennis, like lawn tennis, involves hitting a ball across a net, it is played on an asymmetrical court with walls (off which the ball may be played), sloping roofs (known as ‘penthouses’) around 3 sides, a number of openings (including the ‘dedans’, which is at the west end of the Earlsfort Terrace court) into which the ball may be struck, and other distinctive features including the ‘tambour’, a vertical buttress off which the ball may be deflected across the court. It is a game which favours strategy and accuracy at least as much as power and speed; players of all ages can thus compete effectively — a feature which is assisted by a worldwide handicapping system, administered online. Illustrations, including diagrams, of real tennis courts are appended to this letter of observations.

3. The Dublin court

Among the buildings the subject of the above planning application is the only surviving real tennis court on the island of Ireland (there is another on Lambay, a private island, though it is of atypical design, open to the sky, and in poor repair). The Earlsfort Terrace court was built in the 1880s by the Guinness family; it was the venue for the World Championship in 1890; and it was given to the people of Ireland — as part of a larger property including what is now Iveagh House, and the Iveagh Gardens — in 1939. In a letter written in anticipation of the making of his gift, a copy of which he sent in May 1939 to the Taoiseach, Eamon de Valera, Lord Iveagh, the donor, observed that the real tennis court ‘is unique in its way and might be appreciated by players in Dublin.’

The Earlsfort Terrace court is distinctive among real tennis courts in that Galway limestone slabs were used to line its walls and to pave its floor, and thus form the playing surface of the court.

4. Real tennis in Ireland

Several real tennis courts were built around the UK, the US, and Australia in the closing decades of the 19th century; the construction of the Earlsfort Terrace court coincided with that growth period, but it by no means represented the arrival of the game on this island. The real tennis historian David Best has identified references to real tennis courts in various parts of Ireland, with the earliest mention being to a court in Dublin castle in 1361. He reports on courts in Armagh, Cork, Dublin (at least 8, not including that on Earlsfort Terrace), Kilkenny, Laois, and Limerick, and on references to the playing of tennis in Ireland from the 14th century onwards. His February 2012 article is on the IRTA website.

THE PROPOSED DEVELOPMENT

5. The application and the real tennis court

The IRTA does not object to the development of a National Children’s Science Centre; indeed, such an educational facility could make a positive contribution. However, the IRTA considers that the appropriate use of the real tennis court is the playing of real tennis. The proposal contemplates that the main part of the science centre should be in the north wing of the former UCD premises (‘the Butler building’), and in a new building at the back of the National Concert Hall site next to the Iveagh Gardens. The real tennis court is to be linked to the main part of the centre by a tunnel, which seems a rather elaborate means of bringing two entirely separate buildings together (they are, after all, only a few yards apart across what is currently — and is proposed to be — open space at surface level). There is no natural connection between the large grey Butler building and the red brick real tennis court, which deserves — architecturally but also in terms of its distinctive function — to be recognised and celebrated in its own right. It seems extraordinary that so valuable a protected structure as the real tennis court should be considered as an appropriate subsidiary venue, housing a ‘temporary interactive display space’, ancillary to the science centre in the Butler building and new complex. An exhibition hall obviously does not require the features of a real tennis court. Smooth bare stone floors and walls, without electrical sockets or other fixtures or fittings, are surely not ideal for the mounting of interactive science exhibitions in the 21st century? Would it not be more appropriate — and indeed convenient — for temporary exhibitions to be held in another space / other spaces on the proposed development site, perhaps in the building which is set to be demolished, in the existing north wing of the Butler building, or in a purpose-built structure?

6. The application and the real tennis court in the context of development policy

Dublin City Development Plan 2011–2017

Dublin City Council identified ‘six broad themes which are integral to the future growth and development of the city’ (page 7, paragraph 2.2). The third of these is ‘Cultural — Making provision for cultural facilities and protection of our built heritage throughout the city and increasing our awareness of our cultural heritage and built heritage’.

To adopt the real tennis court, a protected structure unique in Ireland, as a venue for temporary science exhibitions, would surely be to miss a real opportunity to return it to the use for which it was designed and presented to the State, and thus to increase public awareness of the cultural and built heritage of the city.

Dublin City Council aims at ‘Fostering the City’s Character and Culture’ (page 23), and ‘fully recognises that Dublin’s built and natural heritage is both a major contributor to the city’s character and is a unique resource that attracts tourism’. Furthermore, ‘The city’s built heritage makes it unique. Key to the approach of this plan is the balancing of the needs of a growing, dynamic city with the need to protect and conserve the elements that give the city its identity.’

The real tennis court, as a protected structure and the only such building in Ireland, is part of that heritage and that identity, and it has an important — and long neglected — role to play in enhancing the character of the city and attracting tourism. If the court were in use it would not only provide a distinctive sports facility for local players, but would also attract visiting real tennis players from abroad to Dublin in order to play.

Dublin City Council has pursued a very positive policy (see, for example, page 84, paragraph 6.2) of delivering and managing a range of community / sports centres, swimming pools, tennis courts and playing pitches, as well as recognising the expanding role of sport and recreation through publication of the Dublin City Sport and Active Recreation Strategy 2009-16. It would be entirely inconsistent with this policy for the real tennis court, a unique sports facility for Ireland, to be allocated a role as an exhibition hall, rather than being returned to use for the game of real tennis.

Dublin City Council considers (page 95, paragraph 6.4.7) that ‘The development of sport and recreation are important in encouraging a sense of wellbeing and social contact … [and] … acknowledges the very important role that sporting and social clubs play in enhancing the social and recreational life of the city’s communities. Facilities for both formal and informal recreation and catering for persons at all stages in their lifecycle, all abilities and diverse cultures are required. Dublin City Council will liaise with sporting organisations to ensure where possible that the City Council responds to the needs of sports clubs and communities in the provision of quality facilities.’

If the court is not made available for real tennis, and permission is granted to the current proposal, the shell of an existing high quality sports facility will remain in central Dublin — present but unusable — with its potential untapped. It should be noted that real tennis is a game enjoyed competitively by persons over a wide range of ages (IRTA events have seen participation by children and by adults in their 80s, as well as players representing every decade in between), not least because it favours accuracy and strategy at least as much as power and mobility around the court, and it thus seems tailor-made to fulfil the Council’s objectives as set out above. The IRTA would be very happy to liaise with DCC to bring the real tennis court back into play.

Chapter 7.1 of the Plan relates to ‘Culture’, and emphasises not only the attraction of vibrancy and diversity of activity, but also that ‘protection and enhancement of the built heritage is essential, both for the cultural and economic success of the city’ (page 102). The return of the real tennis court to use would not only protect and enhance a unique element of the built heritage of the city, it would also revive a distinctive facility which would heighten the profile of Dublin as a business venue and tourist destination.

The IRTA considers that the game of real tennis and the real tennis court on Earlsfort Terrace are both part of the cultural fabric of the city. As set out in brief above, the game has a long history in Dublin as indeed in Ireland as a whole, and the Earlsfort Terrace court holds inherent interest on architectural and historical grounds, as acknowledged by DCC, but also as a sporting venue.

DCC considers it ‘important to increase public awareness of the importance of the legacy and riches of the built heritage’ (paragraph 7.2.3, page 114), and regards finding ways to keep the buildings of the city’s built heritage in active use as ‘a key challenge’. The obvious way to keep the real tennis court building in active use, while at the same time increasing public awareness of its character, importance, and legacy, is for it to be used for its intended purpose, real tennis. The return of the court to use is the logical next step in protecting and enhancing this element of the city’s built heritage. Indeed, any other approach would be contrary to the objectives of the DCC (and would surely also be inconsistent with the aspirations of Dublin to World Heritage Site status — see page 115, and FC57 on page 121, and Ireland’s submission to UNESCO of 8th April 2010).

It is the policy of DCC (FC26, page 115) ‘To protect and conserve the city’s cultural and built heritage; sustaining its unique significance, fabric and character to ensure its survival for future generations.’ Part of the ‘unique significance’ and ‘character’ of the real tennis court is its function, and its ‘fabric’ was designed with that function in mind. The best approach to the protection and conservation of this unit of the city’s cultural and built heritage, and that which is most likely to sustain its unique significance, fabric and character for future generations is for it to be returned to the use for which it was conceived and built.

The real tennis court is a protected structure, and it is the policy of DCC (FC30, page 116) ‘To protect these structures, their curtilage and the setting from any works that would cause loss or damage to their special character.’

However, the policy of DCC goes beyond merely ‘protecting’ these structures; it also involves positive obligations, set out in FC31, which provides that it is the policy of DCC ‘To maintain and enhance the potential of protected structures and other buildings of architectural/historic merit to contribute to the cultural character and identity of the place, including identifying appropriate viable contemporary uses.’ The appropriate use of the real tennis court is real tennis, and the IRTA has conducted analysis that concludes that such use would certainly be viable. The return of the court to its original use would clearly maintain and enhance its potential to contribute to the cultural character and identity of the place.

The policy of DCC is set out further in FC32, which is ‘To encourage the protection of the existing or last use of premises listed on the Record of Protected Structures where that use is considered to be an intrinsic aspect of the special, social, cultural and/or artistic interest of those premises. In considering applications for planning permission in respect of a change of use of any such premises to take into account as material consideration the contribution of the existing or last use of that structure to special, social, cultural and/or artistic interest of those premises and / or whether the new use would be inimical to the special interest identified.’ There is no doubt that the use of a real tennis court for real tennis is to be considered ‘an intrinsic aspect of the special … interest of the premises.’ The real tennis court has been used, since its donation to the people of Ireland in 1939, as a gymnasium, as an engineering laboratory, as offices for a State-supported archaeological project, and then most recently, on foot of a temporary planning permission, as temporary accommodation for the Irish Museum of Modern Art. None of these uses contributed to the special, social, cultural or artistic interest of the tennis court — indeed all of them compromised the character of the building, and some involved the removal, alteration, damage, or destruction of essential elements. Real tennis is the purpose for which the building was designed and built, and the playing of real tennis is the use which should be promoted and protected by DCC.

In the event that planning permission should be granted in respect of this application, the IRTA would submit that great care should be taken in ensuring compliance with policy FC38, as set out at page 117, which provides that it is DCC policy ‘To promote the use of planned maintenance programmes and the preparation of conservation / management plans to avoid loss of historic building fabric and authenticity through inappropriate repair work.’ This submission is made in the context of the special requirements of a building designed and built for a particular purpose. It is not sufficient that the building be conserved / restored so as to look like a real tennis court (though the plans as submitted do not in fact achieve even this, as far as the interior is concerned — see below for further detail), it should be a real tennis court. It is essential to the special character of the building that it be conserved / restored to specifications which answer the requirements of the playing of real tennis — anything less would not only be inauthentic, it would also compromise the character of the building, could restrict the proper use of the court should it become available for play at some future time, and would amount to ‘inappropriate … work’.

The real tennis court was given to the people of Ireland in 1939; as such, it is submitted that it falls to be considered as part of the ‘public realm’ for the purposes of paragraph 7.2.5.5 (page 121). In this context, it is the policy of DCC (FC51) ‘To identify and implement positive measures for the enhancement and regeneration of the historic city, improve its physical condition and presentation, sustain its character and authenticity.’ The appropriate approach to the improvement of the physical condition and presentation of the real tennis court, and to sustaining its character and authenticity, must be through its return to use for real tennis. The conversion and adaptation of the tennis court building for use as an exhibition venue would not be a positive measure ‘for the enhancement and regeneration of the historic city’ as it would compromise the character and authenticity of the building, as well as its physical condition and presentation.

The proposed development is in an area zoned Z8 (‘Georgian Conservation Areas’), the objective of which is (page 201, paragraph 15.10.8) ‘To protect the existing architectural and civic design character, to allow only for limited expansion consistent with the conservation objective.’ It is at least questionable whether the proposed science centre, with its substantial new structure immediately adjacent to 3 protected structures, and with its reconfiguration of the relationships between those protected structures, represents ‘limited expansion’, or whether it would ‘protect the existing architectural and civic design character’.

Paragraph 17.10 (page 270) sets out Development Standards for Works to Protected Structures. We welcome the high standards required for such works, and we submit that in this case any works to the real tennis court should take into consideration not only the proper appearance of the court, but also the compatibility of those works with the playing of real tennis (for example in respect of the repair and finish of the floor and walls, the location of openings onto the court, the reconstruction of penthouse walls and penthouses, and the installation of suitable lighting).

We note that at paragraph 17.10.1, Works to Protected Structure, it is provided on page 271 that ‘The interconnecting of adjoining protected structures will only be permitted if size restrictions of the individual buildings otherwise prohibit sustainable usage.’ This plan proposes the construction of a tunnel to connect two protected structures: the real tennis court and the north wing of the Butler building. The two structures have never been interconnected, and were not conceived as part of a single complex. It would be extraordinary to suggest that ‘sustainable usage’ of the north wing of the Butler building was not possible, because of ‘size restrictions’, without the construction of a tunnel connecting it to the real tennis court. The same is clearly true of the real tennis court, which could be put to sustainable use (for example as a real tennis court) without any need for a tunnel or other connection to the north wing of the Butler building.

DCC policy in respect of Development within the Curtilage of a Protected Structure is set out at paragraph 17.10.2 (page 271). We would submit that the proposed development, while it involves certain commendable work to the fabric of the real tennis court building, does not ‘protect the special character’ of the real tennis court. Furthermore, the design of the new development does not ‘relate to and complement the special character’ of the real tennis court. As regards the development as a whole, a science centre does not relate to, protect, or complement the character of the tennis court. Fundamental aspects of the ‘special character’ are missing unless the court is returned to playable condition. We note that the application refers to ‘the proposed restoration works offering the possibility of the sport of Real Tennis Building [sic] being played on the court once again’ (Planning Report, paragraph 6.2), but the playing of real tennis seems not to be contemplated on foot of the current proposed development.

DCC policy in respect of Uses and Protected Structures is set out at paragraph 17.10.4 (page 272). We would submit that the proposed use of the real tennis court building as a ‘temporary interactive display space’, attached by means of a tunnel to the rest of the proposed science centre site, is not compatible with the overall objective to protect the special interest and character of protected structures. Indeed, the special interest and character of the real tennis court will only be properly protected if the building is made suitable for the purpose for which it was designed: the playing of real tennis.

Draft Dublin City Council Development Plan 2016 — 2022

The IRTA welcomes particular provisions in the Draft Dublin City Development Plan 2016–2022, including Policy CHC1 which provides (see page 94) not only ‘To ensure that the special interest of protected structures is protected’, but also that ‘Development will conserve and enhance Protected Structures and their curtilage and will … protect or, where appropriate, restore form, features and fabric which contribute to the special interest’ (emphasis added).

It is stated explicitly in the Draft Plan 2016–2022 (paragraph 11.1.5.3, page 95) that ‘The historic use of the structure is part of its special interest and in general the best use for a building will be that for which it was built.’ This directly endorses the position adopted by the IRTA in this submission.

Dublin City Sport & Active Recreation Strategy 2009 — 2016

It would be inconsistent with this strategy to permit the development of a state-owned, world class sports facility (venue for the real tennis World Championship of 1890), which is unique on the island of Ireland, and which is one of relatively few in the world, as an additional display space for a science centre.

7. National Children’s Science Centre, Planning Report (OPW, Feb 2016) & plans

It is striking that there is no mention of the real tennis court building, a protected structure, in the text of Section 1.0 of this report, the Executive Summary. This supports the conclusion that the use of the real tennis court is not actually a central element of the project; indeed, the science centre is mainly to be housed in the north wing of the Butler building, and in a new building at the back of the site adjoining the Iveagh Gardens.

In Section 3.0 reference is made to the Site Notice, which announces ‘the refurbishment and restoration of the … Real Tennis building’. This seems encouraging from the real tennis perspective, and indeed there are positive elements of the proposal in that it involves significant conservation steps. However, examination of the application shows that the tennis court will not in fact be fully refurbished or restored.

The Site Notice announces that ‘The Real Tennis building will be refurbished and restored including the tennis court, stairwell and ancillary spaces.’ The only use identified for the tennis court is that mentioned above, which is assigned in a label on the plans: ‘temporary interactive display space’.

At Section 6.2 it is provided that ‘All polished limestone to the walls and floor [of the real tennis court] will be fully cleaned, restored and re-laid.’ It is not clear what is to happen in areas of the floor where the limestone slabs are missing, or have been broken beyond repair. Appropriate conservation / restoration of the floor would include the replacement of slabs, where necessary, to ensure a uniform surface, to a standard suitable for the playing of real tennis.

Also at 6.2 we learn that ‘The renovated Real Tennis Building can also act as an independent event space with the proposed restoration works offering the possibility of the sport of Real Tennis Building [sic] being played on the court once again.’ The proposal implies that the court — a protected structure — would be returned to a condition in which it might be used for real tennis, the activity for which it was designed. In fact, the proposal seems to come tantalisingly close: the applicant is planning substantial restoration works while omitting essential features of a playable court, and including others which would compromise play. While it is proposed that the tennis court should be restored, with cleaning and re-laying of limestone slabs on the floor and walls, and the closing of 2 doorways currently in the main wall, (i) there is no provision for the construction of penthouse walls / penthouses, and none are now present; (ii) the plan includes a new doorway in the main wall, between the tambour and the net; (iii) the plan proposes the ‘reopening’ of a purported ope on the landing of the staircase at the west end of the building which would breach the playing surface above the dedans penthouse; and (iv) it is unclear whether the floor and walls would be finished to a playable tennis surface. Furthermore, aside from the curious and inconclusive statement quoted above, there is no indication that the court would be available for its original purpose; and restoration of the court to playable condition would be in line with the draft policy quoted above: ‘to protect or, where appropriate, restore form, features and fabric which contribute to the special interest’ of the protected structure (Draft Dublin City Council Development Plan 2016–2022, page 94).

Section 6.3 refers to the use of the proposed new science centre building, adjoining the Iveagh Gardens, ‘“out of hours” … for a variety of purposes such as corporate events, specialist lectures … etc’ which ‘will bring added diversity to the Earlsfort Terrace Quarter’. If it is desired to add diversity to the Earlsfort Terrace Quarter, this might effectively be achieved, in a manner consistent with good conservation practice and in accordance with DCC policies, by making the real tennis court available for the playing of real tennis.

There is very little specific reference to the real tennis court in Section 6.9, but it is mentioned in the context of Lifts: a ‘through car type passenger lift will serve both floors of the Real Tennis building.’ Real tennis involves the use of only one floor level. The sole purpose of the lift appears to relate to the tunnel between the Butler building and the area immediately to the south of the real tennis court. It is misleading to indicate that the lift ‘will serve both floors of the Real Tennis building’: in fact the lift will move between the proposed new basement to the south of the tennis court (the level at which the tunnel arrives) and the ground floor (the level of the floor of the tennis court).

It is remarkable that the proposed entrances to and circulation around the real tennis court continue to disregard flagrantly the character, design, and function of the building. While the closure of the double doors in the main (south) wall of the court, and the closure of the door near the tambour, are to be welcomed, only limited effort has been made to use the logical and existing access points from the south side of the building (or indeed the west side). Rather, it is proposed that a (possibly original) doorway opening into the dedans from the south should be blocked up; that a new entrance should be broken in the main wall, this time on the hazard side of the court between the tambour and the net; and that an existing opening, at the hazard end of the south wall, is to be enlarged from being a window to being a door to provide access from the court (in fact from under the grille penthouse) to lavatories and stores. This last opening may not in fact impinge on the playing area, if it falls in its entirety beneath the grille penthouse. If the opening protrudes beyond the penthouse wall then it would interfere with the playing area of the court, would be inappropriate, and should be adjusted.

A further new entrance, creating a new opening in the shell of the building, is proposed at the Earlsfort Terrace (east) end of the north wall. This opening would not in fact directly interfere with the playing surface, as it would appear to be under the level of the top of the penthouse. No particular explanation is offered for its inclusion in the plan. If the penthouses were to be reinstated (as would be appropriate), anyone or anything arriving through this door would gain access to the lavatories and stores via the passage beneath the grille penthouse, and would only gain access to the court at the opening at the net. In any event it would surely be incompatible with conservation of a protected structure to be arbitrarily breaking a new opening in a face of the building hitherto devoid of doorways, where that new opening contributed nothing to the character of the building, nor to the use for which it was intended, and with no obvious indication of the reason for its inclusion?

It is encouraging that the existing roof light is to be repaired and replaced where necessary to best conservation practice. The glazed section of the roof would have been an essential feature of the court at the time of its construction, and perhaps for as long as the court remained in use, as it admits daylight to the court, and may have been the sole source of light by which to see the fast-moving ball. The electric lighting scheme now proposed should be to the appropriate specification to permit the playing of real tennis by artificial light alone, and the light fittings should be sufficiently robust (or protected) to cope with possible impacts from real tennis balls (as at all courts now in use).

It is encouraging that the modern pipework, fluorescent lighting, and other services on the walls and elsewhere on the court are to be removed, and the stone playing surfaces restored. It would of course be necessary to ensure that the surface of the stone on the walls and floor is finished appropriately for the playing of real tennis. An element of this playability will relate also to the re-laying of stone slabs on the floor, given that it is contemplated that the slabs should be re-laid on concrete, rather than on the original trestle system. Care must be taken to ensure that a playable court is achieved.

Certain chase markings (the lines and numbers on the floor and walls) survive, particularly on the floor along the south (main) wall. If the court is to be properly restored, all of the floor markings will need to be reinstated, and it would be appropriate for the existing lettering / numbering style and other decorative themes to be adopted. Furthermore, if the court is occasionally to be used other than for real tennis, the floor (and its markings) will need to be protected.

The proposed removal of the internal blank covers over the window openings is welcomed, and the conservation of the louvres. It is proposed that glazed screens be installed inside the louvres, to be mechanically adjustable to regulate ventilation. These glazed screens should be capable of withstanding occasional glancing blows from real tennis balls.

8. Architectural Heritage Impact Assessment (Blackwood Architects, February 2016)

We would observe as a preliminary point in respect of this Assessment that while the author reports ‘numerous site visits between November 2014 and January 2016’, there is no reference to any visit to an operating real tennis court, nor to consultation of any person with expertise in the design, construction, maintenance, or use of a real tennis court building for its intended purpose. The IRTA is in a position to facilitate such visits and or consultation, on request.

In the ‘Introduction’ on page 5, following a summary of the basic interventions proposed for the site as a whole, and in particular for the protected structures, it is concluded that these ‘will provide the historic buildings with the increased flexibility required to allow the mostly redundant areas on all levels to acquire a much needed new use.’ It is submitted that the appropriate use for the tennis court building is its original use, the playing of real tennis, and that there is thus no need for the ‘increased flexibility’ mentioned. Even if real tennis were not the sole user of the court, it is submitted that a complete playable real tennis court has sufficient size and ‘flexibility’ to permit numerous other uses.

At page 10 we find the following description of an area on a staircase at the north west corner of the tennis court building: ‘There is a blocked up arch on the half landing that may originally have been the access point to the Dedans (high level viewing area), a structure that has now been lost.’ This hypothesis, while perhaps understandable from an architectural-historical reading of a blind arch, and a misunderstanding of the illustration which appears as Image 1.09, is surely incompatible with any basic awareness of the layout of a real tennis court. The blocked up arch would, if opened, have breached a playing wall of the court itself. The dedans is not a ‘high level viewing area’: it is an opening the lower edge of which is c. 3’ 6” from the floor level of the court, and the upper limit of which is c. 7’ from the floor (it would have been at the west end of the Dublin court). It does serve as a viewing area, but access to it would have been at (or near) the level of the floor of the court. It is true that at a number of courts strong glass has in recent years been used to provide additional viewing points into real tennis courts (Washington DC; and one of the 2 courts at Prested Hall, in the UK, are good examples of courts at which this has been done), but these are a feature made possible by later 20th century technology. It is very unlikely that the Earlsfort Terrace court would have had an opening at the location suggested (though a small wooden hatch might just have been possible) — in all likelihood there is a limestone slab on the wall of the court behind the blind arch. However, installation of a glazed panel, provided it was carefully engineered to be of consistent bounce with the surrounding playing surface, and provided it did not interfere with the dedans penthouse or other features, would not necessarily be incompatible with the playing of real tennis on the court. It might be regarded as an unwarranted interference with the fabric of the protected structure, given that it could almost certainly not be regarded as reinstatement of an historic feature.

Also at page 10 it is observed that ‘The original entrance route to the west … is no longer in use … [and] A newer entrance has been created in the south elevation wall.’ This entrance in the south wall certainly post-dates use of the court for real tennis, as its presence is incompatible with the playing of the game.

We are concerned (admittedly on the basis of a catalogue of dimensions of various courts, rather than actual on-site measurement) that the estimate of the floor area of the court at page 10 may be overstated by some 75 square metres.

While the footprint of the penthouse walls is traceable on the floor of the court (see page 10), it is significant also that the junction of the penthouses with the internal faces of the walls of the building is also discernible, and what appear to have been supporting beams along those walls survive at least in places.

The tambour is an obvious and distinctive feature of the tennis court, and is visible beside the staircase which currently leads to the upper floor at the east end of the building (see page 10). The doorway inserted in the south wall of the court near the foot of the said staircase also post-dates the use of the court for real tennis, and its presence compromises the court as a venue for the game.

There is no mention of the damage to the ‘out of play’ line in the upstairs area at the east end of the south wall, which must surely have been inflicted in the period since the installation of the upstairs offices.

The plans on page 109 appear to be mistitled. The first of the 2 plans (labelled ‘Ground Floor Plan’, but in fact showing the layout of the upper sections) includes an opening from the ‘landing’ on the staircase at the west end of the building which is not in fact present (see comments on this above).

Among the features which appear not to have been noted are the distinctively narrow stone slabs in the floor at the level of the net (in area G6); the windows in G6 are described as ‘blank’ — they are louvred on the exterior and were blocked in the context of recent temporary use as exhibition space (windows in the office area upstairs at the east end were glazed with hinged windows at some earlier stage); skirting boards are present in G6, G7, and G8 in areas which would have been under the penthouses, but they are not, of course, in the areas of the court which would have been in play; in G7 and G8 the ‘historic plaster with paint finish’ on the north and east walls is only on the sections of wall which would have been below the penthouses — there are stone slabs on the walls above that level, which forms part of the playing surface; in G8 the south wall is not all partition: the tambour, as well as sections of the main wall, are exposed; and there is no mention of the attic area above the changing room and adjoining room with wood panelled ceiling at the west end of the court, access to which is off the staircase in the north west corner.

The report that ‘the building was vacated by UCD in 2007 and has since remained derelict’ requires qualification. It disregards, for example, the continued use of the upstairs section for archaeological purposes for a period, and the use of part of the building (here labelled G6) as a contemporary art exhibition space for periods in 2011 and subsequently (see an application for temporary planning permission in that context, reference number 2127/12). It was the venue for the launch by Minister Deenihan of a book by Mike Cronin and Roisin Higgins on the history of sporting sites in Ireland, ‘The Places We Play’ (Collins Press, Cork) in October 2011, which opens with a paragraph describing the heritage interest and importance of the real tennis court:

Just off St Stephen's Green in Dublin, on Earlsfort Terrace, is the National Concert Hall. This building, and those surrounding it, were the original home of University College, Dublin. The university as a whole moved to its current site at Belfield from 1964, and closed its few remaining offices at Earlsfort Terrace in 2007. Despite this, the site has not been fully redeveloped, and many buildings retain the look and feel of a university campus. One building in particular seems more overtly abandoned since its former university use. This large brick building, with a pitched glass roof, and standing directly opposite the Conrad Hotel. It is not a particularly pleasing building, and it does not seem to have, at first glance, any aesthetic or architectural value. Inside it lies largely empty, having been used by the University, at various times, as a gymnasium and a chemistry laboratory. There are various lines and markings on the floor and walls of the building, and these, along with the excellent light that pours through the glass roof, give a few clues as to why the building was constructed, and why it remains, to this day, significant to Irish heritage. This building, constructed in 1885 by Edward Guinness, was, and remains, Ireland's only covered Real Tennis court. Guinness lived at 80 St Stephen's Green, and built the court in his back garden (the remainder of which, Iveagh Gardens, was given to University College, Dublin, in 1908). The solid-looking building was constructed with a brick facade, a marble-lined interior and vaulted skylight roof in glass. The court was held in such high regard that the 1890 Real Tennis world championship was played there, and won by British-born American Tom Pettit. In 1939, Rupert Edward Cecil Lee Guinness donated the court to the nation in the expectation that the court would remain in use. Unfortunately, University College, Dublin moved in and the court was used for other purposes.

The report on page 121 that ‘The main court space retains its original shape’ is potentially misleading in that it does not explicitly acknowledge that the area at the east end of the building, to the east of the partition wall, is part of the playing area of the tennis court, and nor does it mention that the penthouses are no longer present. On the same page, Image 4.18 is also potentially misleading in that (a) it does not reflect the full volume of the court (part of which is behind the partition wall behind the photographer), and (b) it refers to ‘original flag stones, markings visible’. This might be taken to imply that the markings which are visible in the image relate to real tennis; this is unlikely, although real tennis markings do survive in places (and would originally have been present on the main wall and on the penthouse walls, as well as on the floor). The appearance of confusion is reinforced further down the same page when it is reported that ‘The floor to the tennis court has a central section of polished limestone with original marking of the tennis lines and the remainder of the floor is of concrete.’ The floor of the playing area of the tennis court would have been of uniform construction. The area of the floor beneath the penthouses (around the north, east, and west sides of the court) is not of stone slabs; the remainder of the floor of the court would have been. The report does not include a photograph of the surviving real tennis court markings, though one is included at Section 5 of the Planning Report, and there is another among the images on one of the drawings.

It is inaccurate to state, as on page 121, that ‘The façade to the south has become internal with insertion of the modern roof’; while part of the façade to the south is indeed now internal, the upper section, including the window openings, is above the level of the modern roof.

The Impact Assessment section occupies pages 125 to 128 of the document; the section dealing specifically with the real tennis court begins two-thirds of the way down the second column on page 126, and concludes at the foot of the first column on page 127. It does not demonstrate any special awareness of the layout or character of a real tennis court. The opening sentence of the tennis court section relates that ‘It is planned to connect the Real Tennis Court Building with the Butler Building via an underground passageway’, but there is little or no assessment of the significance of this new connection between two protected structures — the impact of which, at the very least, must interfere with the independent character and integrity of each of the existing buildings.

It is acknowledged (page 126) that ‘There are significant alterations proposed in all spaces of the [real tennis court] building that will have an impact on the historic integrity of the building.’ These appear to be treated lightly.

The IRTA welcomes the removal of the upper floor and partition walls in the eastern section of the court. While this step will open up a larger space, and will return the tambour to view, the court would only be returned to its original volume with the reinstatement of the penthouse walls and penthouses.

The IRTA doubts very much that ‘the original first floor ope from the staircase to enter the dedans viewing platform’ was ever in fact open, and considers it inconceivable that a ‘dedans viewing platform’ might have been incorporated on the face of the playing wall above the dedans penthouse. The IRTA position on this is supported by the description of the court which appeared in The Irish Times during the World Championship of 1890, the text of which is available on the IRTA website

The proposal to open up this ‘original first floor ope’ is thus misconceived, and is inconsistent with the proper care and conservation of this protected structure. Furthermore, as this is a playing surface, it is likely that the wall at this point is faced in limestone. If an opening were to be made, it would require the removal of limestone slabs which form part of the playing surface of the court.

It is proposed that ‘Two other blocked up opes in the stairwell will also be reinstated’. Given the curious approach to the above ‘original first floor ope’ extreme caution should also be exercised in considering these other two (although they appear to be in the northern and western external walls, so would not directly interfere with the tennis court itself).

The load-bearing capacity of the trestle-built real tennis court floor may well be less than is necessary for exhibitions (it seems to have supported engineering equipment for many years, though it did not emerge from this experience unscathed). In any event, significant work would be required to bring the floor of the court from its current condition to playability. If it is possible for the work contemplated to be carried out without injuring the suitability of the floor for the playing of real tennis, then the structure upon which the slabs rest may well be of limited consequence (other than from the point of view of architectural history and integrity). It is not clear from the report (see pages 126–127) what is to be used in the repair of the floor in areas where the limestone slabs are broken or missing. While it is emphasised that the slabs are to ‘be re-laid carefully … in their original locations as some original court markings still remain on the floor and must be retained’, it is unclear from the report how the playing surface (including the original court markings) would be conserved if the project were to proceed, and the floor were to become a busy exhibition space. It is noted that the reports of Linzi Simpson and Blackwood Architects identify different (and both, we would submit, inaccurate) sources for the stone used in the court.

The creation of a ‘large opening’ in the north wall of the building would clearly compromise the character of this protected structure. However, from the point of view of the playing of real tennis, provided the opening was entirely below the level of the top of the penthouse, it need not impinge on the playing surface. Whether or not this door in the north wall is contemplated as the point of access for ‘temporary interactive displays’, it would be important to ensure that they could be moved on and off the court without interfering with the penthouses and penthouse walls which are essential features of an operational real tennis court. It is somewhat bizarre that the report should claim that the proposed large opening in the north wall of the building ‘is an essential intervention to make the court a usable space.’ Obviously, the court is a usable space as a real tennis court without any such intervention, but it has also been used as an exhibition space by IMMA, and as a civil engineering laboratory for UCD without any need to break a large entrance in its north wall.

The fact that openings have in the past been broken in the main (south) wall of the court should not be regarded as precedents for good conservation practice. The character of the court is dramatically compromised by the creation of openings on the playing surfaces, and the main wall is a key playing surface. The IRTA submits that good conservation practice dictates that such openings as are already present should be blocked, and no further breaches should be permitted. If access is required through the south wall of the court, ‘to provide a link to the foyer beyond’, this should be by way of a door under the dedans penthouse and or under the hazard penthouse.

It is noted that where existing opes are to be blocked up, the wall finish is to be reinstated. This will involve the installation of slabs of limestone on the wall, the source of which should be carefully considered.

The paragraph dealing with the roof (page 127) appears once again to demonstrate a failure by the author of the report to appreciate the distinctive character of the building as a real tennis court. While the glazing itself is modern, the work carried out to the roof in the late 20th century appears not only to have respected ‘the original design intent’, but also to have in large measure retained and reused the original timber and metal structure. It is altogether unclear what is meant by the assertions that the roof structure ‘is not fully in keeping with the historic building’, and that ‘the presentation of the overall building would be greatly enhanced if [the roof structure] were replaced with a roof respecting the original design intent.’ This real tennis court, as so many others of its time, would have depended largely if not entirely on natural daylight for illumination. There is specific reference to the glazed roof in the 1890 Irish Times article already mentioned. The glazed ridge of the roof was an essential element of the building, and remains a key feature, to be understood, appreciated, protected — and, ideally, used for its intended purpose.

The enclosed area to the south of the court is not part of the court, but is surely a candidate area for the provision of changing rooms and other appropriate facilities ancillary to the use of the building for real tennis. The proposed new wall at the northern end of the car park of the NCH, complete with windows, will surely jar somewhat with the presentation of the east end of the tennis court, and the extension to the south of the gable wall, onto Earlsfort Terrace.

It seems extraordinary that the author of the report should declare that ‘Overall the interventions proposed for the Real Tennis Court are positive despite the loss of some historic fabric and considerable opening up works.’ There appears to be little appreciation in the report of the impact any of the proposed steps will have on the building as a real tennis court. The apparent lack of consultation in this regard is surprising — given the importance of the function of the building to its design, and to its heritage interest — and is certainly regrettable.

It is striking that the author observes that ‘It is unfortunate … that … a large door [must be] provided to the rear’, by which reference is presumably being made to the north side of the building. The north side of the building has only been the ‘rear’ in the context of the opening of doorways in the main (south) wall of the tennis court, which presumably took place during the use of the building by UCD and the OPW. The main (and in all likelihood the only) entrance to the playing area of the real tennis court would have been at the net, under the penthouse on the north side of the building.

As mentioned above with reference to another comparable comment in the report, it is scarcely credible that the author should claim that ‘these changes are essential for the practical use of this building.’ It is also peculiar that the author should comment that ‘As the displays are all temporary it is conceivable that the court could be reinstated in the future if required.’ The application contemplates that the real tennis court building should serve as ‘temporary interactive display space’, which seems to be a very vague, broad, and open description. Any display materials, remaining on site only temporarily, would need to be demountable and transportable. Good practice dictates that one should avoid damaging a protected structure and that, insofar as possible, the character and fabric of such structures should be retained, protected, and conserved. Furthermore, the real tennis court is required for real tennis: it is the only example of a real tennis court of conventional design in Ireland, and the only one of any description on the island of Ireland (there is another, somewhat unusual and open to the sky, on Lambay). There has been an annual Irish Real Tennis Championship since 2003, but every year the participants have been obliged to travel abroad in order to participate.

The current proposal is not the only viable and sustainable option for the real tennis court; in 2012 the IRTA presented a costed plan, with design details, for the return of the court to play. The tennis court does not require a ‘new use’, and it need not, absent this proposed science centre, ‘remain redundant’. It stands as a protected structure with its own valid and viable purpose, and its own valuable integrity and identity — it certainly does not need ‘direct access … from the Butler Building’ as a means of providing it with a raison d’être. The IRTA, with the substantial and significant support of the international real tennis community, remains ready to take on the task of creating a viable real tennis court and club.

The IRTA takes issue with the conclusion in the final paragraph of the document (page 128), insofar as it claims that the proposals regarding the real tennis court ‘have minimal impact on the historical integrity of the building.’ We would also observe that this final paragraph appears to conflate the north wing of the ‘Butler Building’ and the real tennis court into a single building, which is obviously an unfortunate error — not least given that the creation of an underground tunnel connecting these two protected structures is a central part of the plan.

CONCLUSION

9. The role of the IRTA

The Irish Real Tennis Assocation has developed links with organisations and individuals with expertise in connection with real tennis, and with real tennis courts, and is keen to assist with the return of the Earlsfort Terrace court to playable condition and with the creation of a vibrant real tennis club for the people of Ireland.

10. Tourism

There are relatively few real tennis courts in the world, and the people of Ireland are fortunate to have been presented with one in 1939. If it were returned to use, it would not only provide a distinctive sports facility for the country, it would add another country to the select list of those with active real tennis courts, and it would also attract players from abroad to visit Dublin to use the court. It is the policy of DCC (RE30, page 143 of the Dublin City Development Plan 2011–2017) ‘To promote and enhance Dublin as a world class tourist destination for leisure, culture, business and student visitors’, and (RE33, page 144) ‘To promote and facilitate sporting, cultural and tourism events as important economic drivers for the city’. An active real tennis court in Dublin would draw players to the city from clubs around the real tennis playing world. The IRTA frequently receives inquiries from real tennis enthusiasts wishing to visit the court, even though it is not playable (another, from Americans who will be in Ireland in early May, reached us only this morning).

11. Public building

This is a public building, given to the people of Ireland in 1939. It was built by Edward Cecil Guinness, and was presented by his son who envisaged that it might be enjoyed by real tennis players in Dublin. There has been only very limited public access to the building since 1939; it was used by UCD and by the OPW for their own purposes for several decades, and the current proposal sees the court as a kind of satellite building to house exhibitions for a science centre. It does not return the court to playable condition, and it does not appear to permit or contemplate the playing of real tennis at any foreseeable time (despite reference in the Planning Report to the possibility of the game being played in the future). If the current proposal were to proceed, it would restrict public access to this State-owned building to paying visitors to the science centre (there are only a few state-owned real tennis courts: that at Hampton Court is on the tourist itinerary, and has a public viewing gallery for visitors; that at Fontainebleau is often open for inspection by interested tourists); it would fail to restore essential features of the court; and it would greatly compromise the prospect of a return of the building to the use for which it was originally designed and for which it has, among real tennis players, remained so well known.

12. What could be done?

It is not at all clear from the application that the real tennis court is an essential part of the science centre development; it is at best a satellite, connected to the Butler building by a rather elaborate and surprising tunnel. A relatively small additional investment, and relatively small adjustments to the current proposal as it relates to the real tennis court, would not only return the court to its original configuration, but would also afford the potential for it to be used for its original purpose, in accordance with good building conservation practice. It would thus be a sporting venue but would also emerge as a distinctive and attractive heritage building, unique in Ireland, and a particular magnet for enthusiasts for the game from around the world.

13. Enclosed with this letter of observations is the sum of €20.

Yours faithfully,

Mike Bolton

Chairman

Attachments

The IRTA submission included four attachments:

(Image credits and sources: Irish Real Tennis Professionals Association (cutaway diagram); Brodie Design, Horacio Gomes (Newmarket and Jesmond Dene photos); Atethnekos (overhead view).)

As received / scanned by DCC

The scanned copy made available by DCC to the public is available at:

(Unfortunately this link is not completely reliable. If it doesn't work, try going directly to the main page for the application, clicking on the 'View Documents' tab, and paging through to the 'Irish Real Tennis Assoc.' comment.)